Teaching is hard.

I still remember standing alone in my classroom the day before school started. I had finished arranging the desks, putting up the quintessential science posters, and reflecting on how great my first year as a high school teacher would go. I stood there, looking into the future with wide-eyed optimism fueled by a dose of naivety. I had a firm grasp on my content and imagined how easy it would be to pass this knowledge onto my students in the same way as individuals such as Bill Nye had done for me. However, teaching is not as simple as distilling and passing down knowledge to a class of attentive scholars. It is a demanding position where the teacher must establish a dynamic balance of navigating the undulating terrain of skills, emotions, and cultures brought about from the 30 differing life histories of the students.

The fundamental issue I encountered during my first year of teaching revolved around classroom management. During this time, I quickly came to discover being autonomous as a teacher can be both a blessing and a curse. My school serves predominantly white students from high socio-economic backgrounds. Because of these demographics and societal makeup, teachers at my school are treated with an attitude of professionalism. By this, I mean there are very few school-wide discipline policies, nor are there behavioral expectations aside from achieving academic success. Instead, all policies and expectations fall onto the individual teachers to develop and implement in their own classes. Unfortunately, as a first year teacher, these were policies I was not adequately trained or ready for. While reading This Is Not a Test (2014) by José Luis Vilson, I was transported back to my classroom in nothing short of a literary Proustian moment when Vilson described one of his most challenging classrooms:

After the requisite ten minutes it took to settle them down at the beginning of class, they finally would sit down and start writing. But the talking was absolutely incessant throughout my lesson and anything I could muster resembling a sequence of thoughts would fall apart. By the twenty-fifth minute of class, I just went straight to the kids who wanted me to teach and focused on presenting the lesson to them (p. 134).

I grew increasingly frustrated as students disengaged themselves from the course by speaking over me. Eventually I fell into a pattern of excusing students from the classroom and having them sit outside in the hallway. Such a strategy quickly backfired on me as lessons ground to a halt, and behaviors did not change. The same students continued to be disrespectful, and round and round in the negative feedback loop we went. Ironically, the escape from this circular pattern was in another circular pattern— connection circles.

BRINGING A RESTORATIVE FRAMEWORK TO THE CLASSROOM

My experience with connection circles began during March of the 2014–15 school year after I attended a seven-hour professional development course entitled “Restorative Practices in the Classroom.” This course was provided by my school district and was facilitated by the Longmont Community Justice Program (LCJP – www.lcjp.org). During this course, I was taught that connection circles are a subset of a larger system of practices known as “Restorative Practices.” These practices adhere to a basic set of principles and values as expressed in the 5 R’s: Relationship, respect, responsibility, repair, and reintegration. The essence of a restorative philosophy is that relationships are affected by rule-breaking, wrongdoing, or conflict and can be healed by a respectful process that offers students the opportunity to take responsibility for how their choices have affected the person(s) most directly harmed, the school community, and themselves.

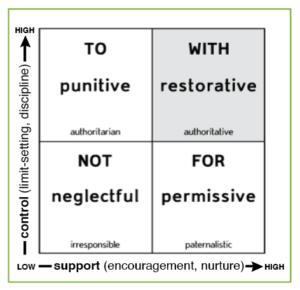

This framework served as a paradigm shift for me as my attention before rested on a punitive approach rather than a restorative approach. The underlying premise of restorative practices rests with the belief that people will make positive changes when those in positions of authority do things with them rather than to them or for them (Wachtel, 2013, p. 3). This idea is summed up in the Social Discipline Window (SDW) (Figure 1), which demonstrates that a restorative approach requires a balance of high levels of control/limit setting with high levels of support, encouragement, and nurture.

Figure 1. Social Discipline Window (Wachtel, 2013, p. 3)

As many first-year teachers tend to do, I defaulted towards the “For” square. I desperately wanted students to like me and felt the best way to accomplish this was to act as more of a buddy. I had lax rules and control, treating students similar to colleagues. Unsurprisingly, this system had the opposite effect of what I intended. Students did not respect my authority and did not take what I deemed important seriously. These behaviors would cause me to overshoot in the SDW into the punitive square when I would send students into the hall. In reflecting on the SDW, I came to the realization that my favorite teachers were the ones who fell into the “With” square; these teachers were warm and caring but also had very specific limitations and expectations in their classrooms. I wanted to push myself into the “With” square; all I needed was a practice to get me there.

CIRCULAR REASONING

Connection circles are a relationship building process used to promote understanding, share experiences, build relationships, and establish a circle practice. To begin, I took my class into the hallway where we all sat cross-legged in a circle. I then introduced the connection circle by stating its purpose and establishing very specific ground rules provided to me by LCJP (here we come to the limit-setting found in the SDW). Rules included:

- Please listen and speak with respect: language—both verbal and nonverbal—can be quite powerful.

- Respect everyone’s privacy—only tell your own story.

- Share time fairly.

- Please speak only when you have the talking piece.

- As the facilitator, I may need to speak to move things along.

- You may pass, but help us remember to come back to you.

Once all the rules were in place, I then introduced the talking piece by explaining the significance of the object we passed to indicate the speaker and how it related to one of my questions. The first day I used a toy turtle and stated how it was one of my most-prized possessions because my friend, a friend who passed away, bought it for me while he was on vacation. Because I shared this personal account with my students, they immediately realized the connection circle was important to me and that they should respect the practice. With this, I then asked the question: “If you could go on a dream vacation, where would you go and why?” This question was followed by, “If you could have any superhero power, what would it be and why?” My last question was more class related: “What is one topic from this unit you have mastered, and one you feel less comfortable with?” Although the first two questions seemed blatantly off topic such questions are necessary and serve as a foundation for future practices. Connection circles function best if there is a culture for relationship and community building already established. I conducted the connection circles with every class nearly every day.

At this point, I would like to stop and address two questions the reader may be thinking:

- “This sounds fairly elementary; my high school students will hate this.”

- “You said you did connection circles every day? I can’t do that, I don’t have that much time!”

Beginning with the former, I will agree with you. I thought the exact same thing: I just knew my students would hate connection circles. As it turns out, I did not have as good of a read on my students as I thought because they loved it! Within three practices, I had students entering my classroom asking, “Are we going to have a connection circle today?” and “Can I suggest a question for the connection circle?” It even got to the point where I handed the role as the facilitator to the students and they asked their own questions.

The underlying premise of restorative practices rests with the belief that people will make positive changes when those in positions of authority do things with them rather than to them or for them.

As for the more pressing question: yes, I did connection circles almost every single day, and yes, it took a lot of time (each practice takes about 10 to 15 minutes). Paradoxically, though, I ended up with more instructional time because of connection circles. Not only did classroom management issues largely disappear, I was able to tie content into the connection circles. For example, I would hold a connection circle at the end of the day and ask questions like, “If you could write one review question from today’s lesson what would it be?” or “What do you think was the big idea from today’s lesson?” Sometimes I would hold a connection circle at the beginning of class and ask questions like, “What is one thing you already know about volcanoes?” to prime the proverbial pump. Before we started our climate change unit in Earth Science I asked, “If someone had a different viewpoint than you, what is a strategy you could use to work with them?” Connection circles were also wonderful for grooming substitute teachers or handling misbehavior in the classroom (e.g., “What is one expectation you think I have for the class with the sub tomorrow?” and “Who is affected when people get up from their seats without asking?”).

Connection circles were one of the most significant contributions I made to my classroom because of the sheer power they had in restructuring the community and classroom culture. I was able to converse with my students in a way I never would have imagined, which allowed me to learn a great deal about them and vice versa. Additionally, the circles provided a source of structure that allowed me to place limits and expectations in my class that diminished classroom misbehaviors.

Most importantly, connection circles allowed the students to see themselves as part of a community and discover a great deal about one another. In one case, I asked the question, “What is one thing you need to leave at the door today so you can focus in class?” A universal answer among the students was their phones, but one student said, “I need to leave my depression at the door.” It was a remarkable moment to witness students opening up in ways they may never have, and feeling safe enough to do it. I had another student who almost never participated in class. He would seclude himself from group work and never answer questions, even during connection circles. However, after about a month of the circle practice, the student finally answered a question by giving a brilliant answer to “Who would win in a fight, Master Chief or Batman?” From this moment forward the student began to participate actively in class, whether it be in connection circles, group work, or any other social facet of the classroom. Throughout all of my classes walls fell, cliques broke down, and communities were built.

In the spirit of inquiry, I anonymously surveyed my students at the end of the semester looking for input as to how they felt connection circles served the class. The following are two pieces of unedited feedback I received:

I have always loved connection circles. I know that we have them about once every week, and I always look forward to it. They are a great way to keep me relaxed, yet engaged while I listen to others and think of something clever and meaningful to say for myself. These circles create a comfortable place for me and my classmates to learn about each other and have a laugh while we are at it. Sometimes it is nice to discuss a question that isn’t necessarily related to the class subject or unit. When we get back to class, I immediately feel comfortable and ready to learn. I feel relaxed and in the mood to discuss and answer questions, and it seems to me that everyone else is, too. Connection Circles would be great in all sorts of classes, and especially those that require the students to interact with each other and answer questions. I feel like the circles take a lot of tension away when I am called on to answer a question aloud.

And:

The first time Mr. Rasmussen brought the class outside in the hallway to sit in a circle for a connection circle, it was a very welcome surprise. They made it so I could learn something new about the people that sit next to me every day in class that I don’t always get the opportunity to talk to. We would go around and answer a question that had to do with what we were learning in class and then we would answer a fun question. It was never anything extravagant, but when it came time to go back to class I always felt refreshed and more awake. School days are so long and connection circles really helped to break them up so that one class didn’t blur into another.

I wanted to include critical feedback from a student as a counter-argument, but, in all honesty, there was none.

THE ROUGH EDGES OF A CIRCLE

Amazingly, this entire transformation began in March in a single school year. I mention this again in an effort to make the point that it is never too late to renorm. Should you attempt to implement connection circles, I suggest allowing them time to flourish, specifically about two to three months of doing connection circles at least once a week. Though I did it every class (two or three times a week), I understand such a time commitment may be a deterrent to teachers. Admittedly, my students warmed up to it faster than I anticipated, but this does not mean the process was not without its difficulties. I also strongly recommend using a written script/protocol with every engagement, and being very firm with the rules that are laid out ahead of time. For example, one rule states that only the individual holding the talking piece is allowed to speak. After engaging in many connection circles, I slowly became lax with this standard and watched as students began to treat the circle as a social gathering with their friends, completely disregarding what other students had to say. Once this mentality takes root, the connection circle becomes a clique-norming tool instead of a community-norming tool. To alleviate this, I wrote myself a script that I used for every circle and was very stringent about all of the ground rules.

Most importantly, connection circles allowed the students to see themselves as part of a community and discover a great deal about one another.

Because the teacher must be very militant with the rules, the teacher must also juxtapose this with being open and honest with the students. I found that when I truly opened myself up to the students (e.g., describing my talking piece that came from a deceased friend), the students had more respect for the process. One student wrote in her survey:

I have noticed that as a speaking prop, you have brought in some items that are close and personal to you. I’d like to say that I truly appreciate that—it makes me feel like you trust me and see me as a person equal to you. I think that brings us all closer together as a class INCLUDING the instructor (not just the students that know each other from other classes and times). Thanks for that!

The last caveat I would provide is to be aware of class size. Connection circles worked wonderfully in all but one of my classes, where, unfortunately, that class seemed to be too large to manage (38 students). Students had a hard time hearing others, resulting in the blossoming of side conversations and distractions. This was unfortunate because the class was unable to reap the benefits of restorative practices; the pervasive classroom management issues never diminished.

Connection circles are a relationship building process used to promote understanding, share experiences, build relationships, and establish a circle practice.

Connection circles can serve many purposes: building relationships, check-in/check-outs, sharing learning, establishing classroom norms, addressing classroom behaviors, etc. Although I was hesitant about implementing them at first, connection circles had an absolutely transformative affect on my classroom. As José Luis Vilson (2014) states, “Every student, afforded the right amount of patience and understanding, has the ability to excel. Every teacher, with the right qualities, can contribute to a student’s growth as a citizen of the planet” (p. 213). I wholeheartedly agree with this sentiment and argue that restorative practices are one such quality which work to foster classroom community and student resiliency.

In the spirit of connection circles, I will end by saying: I would like to thank you all for listening to my story. As I think about our group of educators, I celebrate what we have achieved and joyfully look forward to hearing about your future success with restorative practices. Thank you again for reading.

Eric Rasmussen works as a Learning Technology Coach at Erie High School and Erie Middle School in the St. Vrain Valley School District. Before serving in this role, he worked as a science teacher at Silver Creek High School in Longmont, Colorado, where he taught biology and chemistry. At Silver Creek, Eric spearheaded the establishment of school-wide restorative practices, and worked with students involved in independent studies at the University of Colorado Boulder in the field of neuroendocrinology. Eric, a former Knowles Teaching Fellow, holds a B.S. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and an M.A. in Curriculum and Instruction. Eric may be reached at rasmussen_eric@svvsd.org.