When I started teaching, I had student loans from both my undergraduate and graduate degrees. I had multiple subsidized federal Stafford and Perkins loans from both institutions, a federal Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) grant, and an institutional loan from my graduate program. I had also qualified for the Assumption Program of Loans for Education (APLE), a California-specific program.

Banks know that they can make a lot of money off of student loans (in a lousy economy many people fall behind on payments), so they are a valuable asset to buy and sell, and as a result I had multiple lenders servicing my Stafford loans. To deal with all these parties, I was completing no less than seven different sets of paperwork at any given time. And yet I never paid a single penny of the roughly $60,000 I owed. (And I’m not in jail.)

I want to make sure to point out that the system is not fair. Math and science teachers (and some other shortage areas like special education) are eligible for Perkins loan cancellation and higher levels of Stafford loan forgiveness; my friends who teach English and history are either not eligible at all or not eligible for as much money. Your benefits might vary based on the institution you attended or the state you live in. I received a special institutionally-based loan, and qualified for a California-based loan forgiveness program for educators. Your credential program or state might not have those benefits. I teach at a low-income school, and your school might not be on the list qualifying you for some programs. Also working in my favor was that my parents and grandparents were able to pay for some of my college tuition, and I received tuition support from another fellowship, so I didn’t have loans above the limits of the forgiveness programs (more about that limit below). Many people graduate with more debt than I did and will probably have to get creative. One day teachers will be fully recognized for the great service they provide society, but we’re not there yet.

This article will give you information about subsidized and unsubsidized direct loans, subsidized and unsubsidized federal Stafford loans, Perkins loans, and TEACH grants specifically. I am not an expert, a financial advisor, or a wizard—I’m just a regular teacher like you. Official websites out there can summarize all the necessary information for you (see below). If your situation is at all complicated (e.g., you have gaps in your teaching time, you started teaching before 2004, etc.), I encourage you to go to those websites and/or call your lender.

How do I know what loans I even have?

To start with, you need to get organized. When I finished my master’s degree, I was not even clear on what loans I had or what company was servicing them. My loans kept getting bought and sold, and I wasn’t paying attention.

Luckily, there’s a website for that. The National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS) has a record of every loan you got and where it is now (see Resources). If you have a loan that is special to the school you attended, like I did, it will not be on that list. But all direct, Stafford, and Perkins loans will show up there.

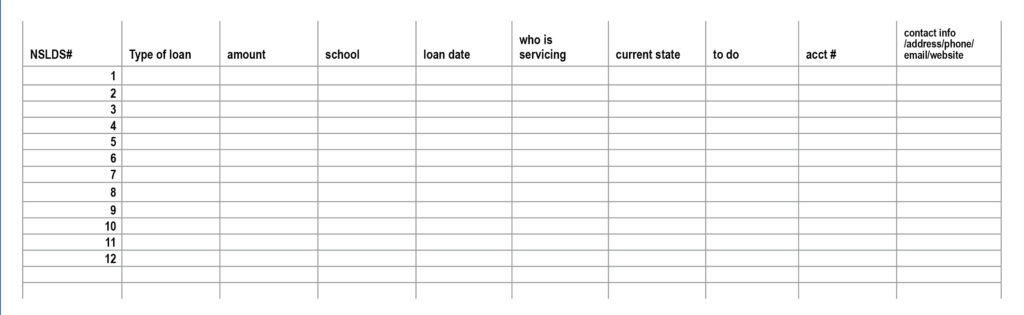

I made a big spreadsheet with all my loans to keep track of all the information, and I cross-referenced it to the NSLDS page (see Figure 1). That way I could keep track of all the various ID numbers, logins, people I’d talked to, email addresses, account numbers, and of course, my progress in making everything disappear. This proved invaluable because I needed to keep track of these things for five years.

Figure 1: Sample loan spreadsheet

What am I eligible for?

The next thing to figure out is your eligibility. Each type of loan has different requirements. Are you a math or science teacher? Is your school on the list of low-income schools? It’s NOT only Title I schools. For a math or science teacher teaching at a low-income school, you get a max total of $17,500 worth of direct and Stafford loans (subsidized or unsubsidized). If you have more than that, you will have to start paying the rest, but you should NOT make payments on that $17,500. I am not going to create any problems by trying to summarize all the particulars here; you’ll have to do some close reading on the applicable websites.

Do I just not pay?

You can’t just stop paying, though: you have to get your loan servicer the memo that you are teaching. Your account needs to be “in forbearance,” meaning you are not making payments in anticipation of forgiveness or cancellation in the future. You need to complete this paperwork close to the time of the start of the school year, and you need your principal’s signature on a letter certifying that you are teaching at the school. Consider getting those signatures before you leave in the spring if your principal is planning a summer break trip to Thailand. The Teacher Loan Forgiveness and Forbearance Application (TLFF) is universal; unfortunately, the Perkins form seems to vary by institutional loan servicers.

You will complete this form every year, and you have to follow up and make sure they received it, they processed it correctly, they applied it, and your account was put into forbearance. Pay attention to dates: it takes them longer than you’d think to process these one page applications, and you may have to ask them to put the account into forbearance while they wait to approve your forbearance (sigh, I know). I encourage you to be pushy.

A Word About Loan Servicers

I’m sure that there is a loan servicer out there that really believes in loan forgiveness programs for teachers. My loan servicers, while they did not come right out and say this, seemed to have a more oppositional institutional philosophy. This meant that every single step I took along the way was met with questioning to the point of absurdity.

An illustrative example: The TLFF states that if the low-income school directory is not updated, the previous year’s list may be used. In my fourth year of teaching, my forbearance request was turned down because my school was not on the list—despite the fact that I had been teaching at the same school the year before and they had approved my paperwork the year before. I searched for schools in California, and found that in fact no schools from California were on the list. The list of low-income schools in California simply had not been issued yet.

The people I spoke with on the phone at my loan servicer were completely unsympathetic. When asked, “So you’re not approving requests from any teachers in California?” I was told that they were not able to comment on anyone else’s application. I had to contact the California Department of Education and finally after agreeing to print out and send in the page from the year before (from the low-income school directory that is freely available online and that they themselves use to check eligibility), my request was approved.

In the meantime, I think I made upwards of 20–25 phone calls, emails, and complaints on websites. It might come from working so much with teenagers, who see the world in a more black-and-white way, but I think I possess more than the usual quantity of righteous indignation. I was working hard for my money, I followed all the rules, and I wanted to keep what was mine.

I encourage you to document the dates you make phone calls. You will never speak to the same person twice, so make sure you have your facts right. I asked to speak to supervisors frequently, and then to their supervisor, if necessary. I became a stronger person. You can, too.

Think You’re Finished?

Towards the end of your five years (or each year if we are talking about Perkins), you apply for “loan forgiveness” (or “cancellation” if we are talking about Perkins). I found this term objectionable because I had done nothing wrong. But so it goes.

This paperwork is even more fun, because you have to get signatures from the principals at every school you taught at in those five years. Not the principal you had, the current principal. For me, this meant introducing myself to someone who had never met me and asking her to sign paperwork saying that I worked at the school five years ago, even though she herself had no actual proof of this fact. (It also meant mailing paperwork to Boston to my own former principal before I found out they needed the current principal’s signature). But you know, if the federal government needs that, who am I to question it?

I encourage you to be extremely careful with this paperwork. You will still have to submit it five times (or more!), but hopefully it will eventually get approved. You have to get Perkins paperwork for cancellation from your institution.

So You Got Yourself a TEACH Grant

My graduate school colleagues and I found the TEACH Grant to be the most inscrutable of all the loans. While I did not fall in this trap, I had friends who had their TEACH Grants converted to direct loans for the most bizarre reasons. My favorite is a friend who had their signed paperwork returned, the signature circled, with a note that said “no signature.” My understanding is that a different company is servicing the TEACH Grant now, and so I hope these problems no longer exist.

What else is there?

Ask around at your school or the institution where you got your master’s degree if there are state-specific or institution-specific programs. I took advantage of California-based APLE, which I came to imagine as an office somewhere in Sacramento where one person sat all day under a pile of 3,000 manila folders. They processed things years after you submitted them. I didn’t know I had been accepted into the program until at least a year after I applied. They were hilarious to talk to on the phone. And then they periodically at totally random times of year sent checks to my loan company, no questions asked. It looks like the program may be over, although the website seems to be at least three years out of date now. Maybe your state has something like that?

Final Thoughts

I hope that you leave this article thinking, “Man, this is going to be a little tricky!” and also, “I really need to get my ducks in a row,” but at the same time, “I think I know where to start,” and “I’m sure glad all these programs exist.” I emphasized the things that will be difficult about this process because I didn’t want you to face them alone, but also because I know you can handle them. You make worksheets for a living; I think you can handle doing a couple yourself.

The fact that there are government programs out there to help you with your student loans indicates that teaching as a profession is valued. You are being further compensated (beyond your measly piddling salary) for providing a public service. I went to a fancy private college and a fancy private graduate school, I graduated with $60,000 of debt, but I am 30 years old, and I am completely debt-free. These programs will not persist if we don’t get out there and talk about their impact on us. This is for you, but it’s also bigger than you. It’s worth fighting for.

Katie Waddle, a Knowles Senior Fellow and associate editor for Kaleidoscope, teaches 9th and 10th grade algebra and geometry at San Francisco International High School in San Francisco, California. She can be a little detail-oriented and, as a born and raised Midwesterner, still struggles with being firm on the phone. Reach Katie at katie.waddle@knowlesteachers.org.