Every day, there are dozens of newspaper headlines, blog posts, and TikTok videos about the ongoing teacher shortage. These varied media sources all detail the reasons why teachers are burnt out and leaving the profession–chief among them are the long hours that many teachers work throughout the school year. If you scroll down to read the comment sections on these pieces (which is never advised), you will hear others saying, “Well, they make up for it with their summers off,” and “They just have to stop coaching and other extras and focus on their classroom.” This begs the questions: how much does a teacher really work during the school year, how does that compare to other full time workers, and how does that compare with the expectations set in district contracts?

While these questions have always been wonderings of mine, they became incredibly pressing to me during the COVID-19 pandemic. I had been involuntarily transferred to the virtual school in August of 2020, with the expectation of returning to an in-person teaching position at my former school the following school year. I had just four days to prepare for teaching virtually, and my schedule was general biology, AP Biology, and anatomy. While I had taught general biology for years, I had no virtual-ready resources in my curriculum, and I had never taught AP Biology or anatomy before. Although I had the perk of working from home, I was working longer hours than I ever had as I learned two new curricula and adapted all three courses to a virtual environment. Through the first six weeks of school, I was working seven days a week. I only took one day fully off—my birthday, which happened to be on a Sunday that year. This was also when the rhetoric that teachers were in favor of online schooling because we were “selfish and lazy” was reaching a fever pitch in the media. By the time December 2020 rolled around, I was not only totally burnt out, I was furious.

So I channeled my anger in the most productive way I could: through a Google spreadsheet. I decided that for the 2021 calendar year, I would track every hour I worked. The seeds of this were planted in the summer of 2019, when I signed up for Angela Watson’s 40-Hour Teacher Workweek (40htw) program. The program is a yearlong course with a monthly focus on a specific area of teaching (e.g., grading, lesson planning, parent communication, etc.) that is designed to help teachers tackle each of these areas more efficiently and reduce the amount of time spent working. Part of the program suggests tracking the number of hours you work so that you can see the impact of the practices taught on the time you spend on teaching tasks. I used Toggl, a timekeeping app suggested by 40htw, to keep track of how long I spent working each day. I plugged the times I gleaned from Toggl into a spreadsheet I had created that would automatically sum my hours for the week, month, and year.

In order to help me clarify the answers to my wonderings, I used the following rules for tracking my hours in the spreadsheet:

- There are two types of hours: required and voluntary.

- All types of hours will be tracked, rounded to the nearest quarter hour.

- Required hours include all district-mandated requirements, such as lesson planning, prep, teaching, grading, district-mandated PD, and any extracurriculars I’m “voluntold” to do.

- Voluntary hours include anything extra to support my teaching, including participating in the Knowles Teaching Fellows Program, pursuing National Board Certification, participating in the 40 Hour Teacher Workweek program, and any extracurriculars/events I signed up for on my own free will.

- Running totals of each hour, as well as the gross number of hours on a weekly and monthly basis will be calculated.

- While being mindful of time limits and distractions, the work should be as close to what I do organically as possible. I want to minimize the effects of changing the outcome by measuring it.

- Commutes between work events (for example, driving to the district office after school for a meeting) count as required hours worked. Commuting from work to a volunteer event (such as driving to a robotics competition after school) counts as volunteer hours. Commutes to and from home or a personal recreation event do not count as hours worked.

With those parameters, I began tracking my hours in the spreadsheet. And, as I tracked my hours I began to get answers to my questions.

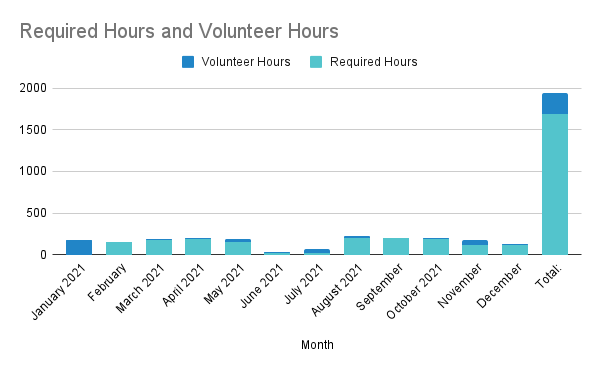

Figure 1

Bar Graph Showing the Number of Volunteer and Required Hours Worked per Month in 2021

Table 1

Summary of the Required, Volunteer, and Total hours I worked in 2021

| Number of required hours: 1689.75 | Number of volunteer hours: 249.25 | Total number of hours: 1939 |

About the Data

The first thing I noticed is that I do spend the majority of my time on the required work of teaching. Doing the math, I found that I spent 87% of my time on these types of tasks, while 13% of my time was spent on volunteer tasks. I also noticed that my volunteer hours vary widely depending on what was going on during that time. There were spikes in volunteer hours during the months I had Knowles meetings (i.e., March, July, and November) and when I worked on a curriculum adoption committee from March through June. My volunteer hours from August through December were largely due to attending football games, plays, and choir concerts to intentionally build relationships with my students as I transitioned back to in-person instruction.

It is noteworthy to mention that 2021 represented an anomaly with my allocation for volunteer hours. Prior to the pandemic, I helped Knowles Fellow Adam Quaal, my friend and coworker, supervise our campus’s For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology (FIRST) Robotics competition team. Our team suspended operations for the first half of 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the start of my return to in-person instruction in August, a series of unfortunate events caused the team to fold, which removed my main source of volunteer hours. While volunteering with this program brought me joy, time with a close friend, and provided a great service to my students, I would spend many hours after school and at least two full weekends a year on this program. Had the team continued, I likely would have had far more volunteer hours.

How do my work hours compare to a traditional, full-time employee?

Let’s take a moment to consider a hypothetical full-time, American employee. For the sake of clarity, let’s name them Alex. Alex has a traditional, 40-hour work week with two weeks of leave a year. If we do the math, we find that Alex works an average of 160 hours a month and 2000 hours a year.

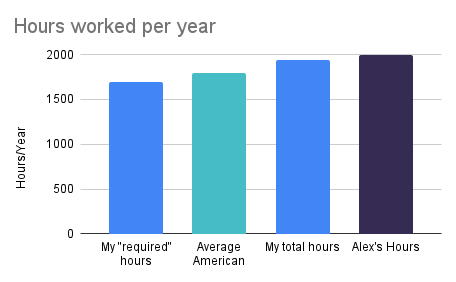

Compared to Alex, I work about the same number of hours a week, but I do have two full months a year that I am not expected to work. This may explain why I worked a total of 61 fewer hours than Alex for the year. However, if we look at the hours I worked during the 10 months I am paid, I spent about 169 hours on required work a month. This puts my work hours on par with Alex’s during the month but it does not factor in the 249.75 hours I spent volunteering for curriculum committees, attending school events, and improving my teaching practices through professional development. If I was to attempt those hours only within the 10 months I am contracted a year, then I would need to work a whopping 194 hours a month, or 48.5 hours a week.

Table 2

Comparison Between My Work Schedule and Alex’s Work Schedule

| Me | Alex | |

| Total hours | 1939 | 2000 |

| Monthly total hours (my hours adjusted for a 10-month teaching schedule) | 194 | 160 |

| Weekly total hours (my hours adjusted for a 10-month teaching schedule) | 48.5 | 40 |

| Average daily hours | 9.7 | 8 |

However, most workers don’t have Alex’s schedule. According to the Organization for Cooperation and Economic Development, Americans worked an average of 1791 hours in the year 2021 (OCED, 2022). So now, we have four data points to compare: my required hours, my total hours, the actual average hours worked by Americans, and finally, Alex.

Figure 2: Bar graph comparing the difference between my annual hours, the average American, and Alex.

Are my contract hours an accurate reflection of what the district expects of teachers? Do my contract hours give me enough time to fulfill the work expectations of my district?

As a high school teacher in my district, I am contracted for 185 work days of eight hours each. In addition to this, I am expected to participate in four “extra duty” events per year, which can include everything from supervising dances, ushering at plays and concerts, or taking tickets at sporting events. If we assume that each event takes approximately three hours, then I am on the hook for 12 additional hours per year. This puts my total contractual obligation at 1492 hours per year.

Obviously, I worked more than that–close to 200 hours more on my required tasks alone! Using my 169 hours/month calculation from earlier, I put in well over a month of extra hours. If we factor in the additional volunteer hours I put in, then I did 447 hours over what my district expects–that’s 2.3 extra months of work, or more days than exist in the entire year.

As shocking as these numbers may seem, I am not alone in struggling with the fact that my contract hours simply do not provide enough paid time to fulfill my work obligations. A September 2022 survey of 4,632 of my colleagues here in California found that the most common words teachers chose to describe their jobs were “exhausting,” “stressful,” “frustrating” and “overwhelming” (Heart Research Associates, et al. 2022).

Lessons Learned

When “exhausting,” “stressful,” “frustrating” and “overwhelming” are the top four words used to describe the working conditions of our profession, it is the sign of a crisis. In that same survey, 58% reported low satisfaction with their workload and 47% reported low satisfaction with their work-life balance (Heart Research Associates, et al. 2022). While I am only a single data point, I would not be surprised to learn that many of these teachers feel the same tension I did between the tasks they are expected to perform and the hours in which they are being paid to complete these tasks. However, it was not until I began to collect my data and see this play out on a spreadsheet that I began to believe that the issue wasn’t just me needing to work more efficiently, but rather a systemic issue.

When “exhausting,” “stressful,” “frustrating” and “overwhelming” are the top four words used to describe the working conditions of our profession, it is the sign of a crisis.

I found this process of collecting and analyzing data to be surprisingly validating. For the months of January through May and then August through October, I was on an “extended day” schedule, meaning I had no prep period during the day. While I felt adjusted to the extended day schedule when I was virtual (January through May), I struggled with the workload when I returned to in-person instruction in August. At first, I felt defective: in theory, I had the same job demands, so why was I so exhausted? And then as I began to look at the data, I noticed that I really was working more! August, September, and October were the months I worked the most hours (spending an average of 6.8 hours a day, including weekends, working during this period), plus I was now also having to spend an hour or more a day in my car, commuting to and from school. No wonder I was feeling burnt out! I began to develop insomnia in late August, and my doctor recommended I go back down to full-time work, which my district managed to arrange a few weeks later. You can actually see the effect of this change with the drop in hours from October through December.

Seeing my feelings play out in the data pushed me to continue working on establishing boundaries between my work and personal life. I have been working on this goal since 2019, which is partly what inspired me to sign up for the 40-hour Teacher Workweek club in the first place. One major question my club work inspired me to focus on was: Am I spending my time on the right things? The answer to this question may vary from person to person, but to me, the “right things” sound a lot like work-life balance: I am effective at my job while also having time for other activities that fill my cup. In a professional sense, the “right things” are the practices that really impact student learning in my classroom, especially lesson planning, grading and giving feedback. While it may be impossible to quantify the specific number of hours I should be planning and looking at student work each week, I found it reassuring to see that the majority of my time is spent on “required” tasks, since time with students, lesson planning, and grading falls under that category of hours. I am the sort of person who needs at least an outline of what students will be expected to do on a daily and weekly basis, or else I get unnecessarily stressed. The flip side of this is that I can also spend four or more hours planning and preparing a one-hour lesson and this takes away from the time I could spend on the “right things” in a personal sense–my family, chores, hobbies, fulfilling volunteer work, self-care, and other things I need in order to be a well-rounded and happy human.

Seeing my feelings play out in the data pushed me to continue working on establishing boundaries between my work and personal life.

Enforcing the boundaries between these different types of “right things” started slowly. At first, it was just taking my work email off my phone so I wasn’t checking it every 15 minutes during the evenings and on weekends. Then I began to create “focus days” at work—days where a particular aspect of teaching like lesson preparation, grading, or organizing took priority. This was because I learned that people are more efficient when they are focusing on one type of task at a time and minimizing switching between tasks, meaning I could do more in less time. It was also around this time that I learned the importance of communicating these boundaries. I noticed that students and parents began to respond more positively to phrases like “I reply to emails between the hours of 7:00 am and 3:30 pm, Monday through Friday” and “I will update grades to include late work on Tuesday” instead of vague explanations like “I will get to it when I get to it.” The final boundary was (and still is!) the amount of time I actually spend working. Knowing when a lesson is “prepared enough” or when students have “enough” grades and feedback, and then going home at this point, is something that I have found is a bit more of a fluid boundary. Some days, I have a pressing personal event, like an appointment or flight, that forces me to decide that I have done enough when it’s time to leave, and other days, I get caught up and work longer than I anticipated. Regardless of the type of day I’m having, I have noticed that I often feel a twinge of guilt when I go home. The cause of this guilt is probably due to a combination of striving to work at my personal best, the high value American culture tends to place on work and career, and the idea that good teachers are like candles that consume themselves to light the way for others. I have to admit that sometimes this guilt (plus the seemingly endless to-do list) tends to be the reason my boundaries “flow” more toward the professional side and less toward the personal. However, as I became more practiced at setting this boundary, I felt the guilt dissipate. It’s still there, but not as strong as it was when I first started on this journey.

In addition to enforcing these boundaries (with admittedly varying degrees of success), I have a few other factors that affect my hours. These factors are ones of privilege: disposable income and experience. By the time I started tracking my hours in January 2021, I had invested $459 of my own money in online-ready curricula for my AP Biology and anatomy classes, since the resources provided by my district had no online components. This saved me hours of time for planning and preparing lessons individually. I also cannot discount the effect of my teaching experience on the hours I worked. When the pandemic began in March 2020, I was in my fourth year of teaching, and so I had developed a wide bag of tricks that helped me be more efficient with lesson planning, teaching, and grading. Had I been a first or second-year teacher without this knowledge and without the privilege of being further up on the salary schedule in order to afford nearly $500 in ready-made lessons, I likely would have spent much more time on this work. The two years of practicing enforcing boundaries and recognizing the value of my time served me well in this experiment, if only to cultivate a greater sense of being “done for the day” while not having a perfect lesson prepped for the following morning.

If you have ever wondered about these questions in your professional life, or if you’ve ever simply wondered if the expectations of your job were out of line with reality, I invite you to begin to track your hours. You don’t have to dedicate yourself to the task for an entire year—you will find interesting data to reflect upon if you track for a month, or even a week. Even if it doesn’t change the circumstances of your job, the data can also prove to be validating, as it was for me. Aside from the personal benefit, I hope for systemic changes as well: If enough teachers track their hours, then we might be able to provide more data points to back up why we describe teaching as more “exhausting” and “overwhelming” than “rewarding” and “empowering.” While teacher workloads are only one of many reasons for mass dissatisfaction with our jobs, this can help illuminate just how out of touch expectations are from district, state, and federal leaders and lead to greater opportunities for systemic change.

Cassie Barker, a Knowles Senior Fellow, works as an instructional coach supporting new teachers with Riverside Unified School District in Riverside, California. Before becoming a coach, she taught biology and chemistry and helped run the FIRST Robotics team at John W. North High School in Riverside for six years. Cassie is passionate about increasing teacher retention through increasing the sustainability of the profession and is always willing to discuss the ways that this can happen. You can reach Cassie at cassie.barker@knowlesteachers.org.